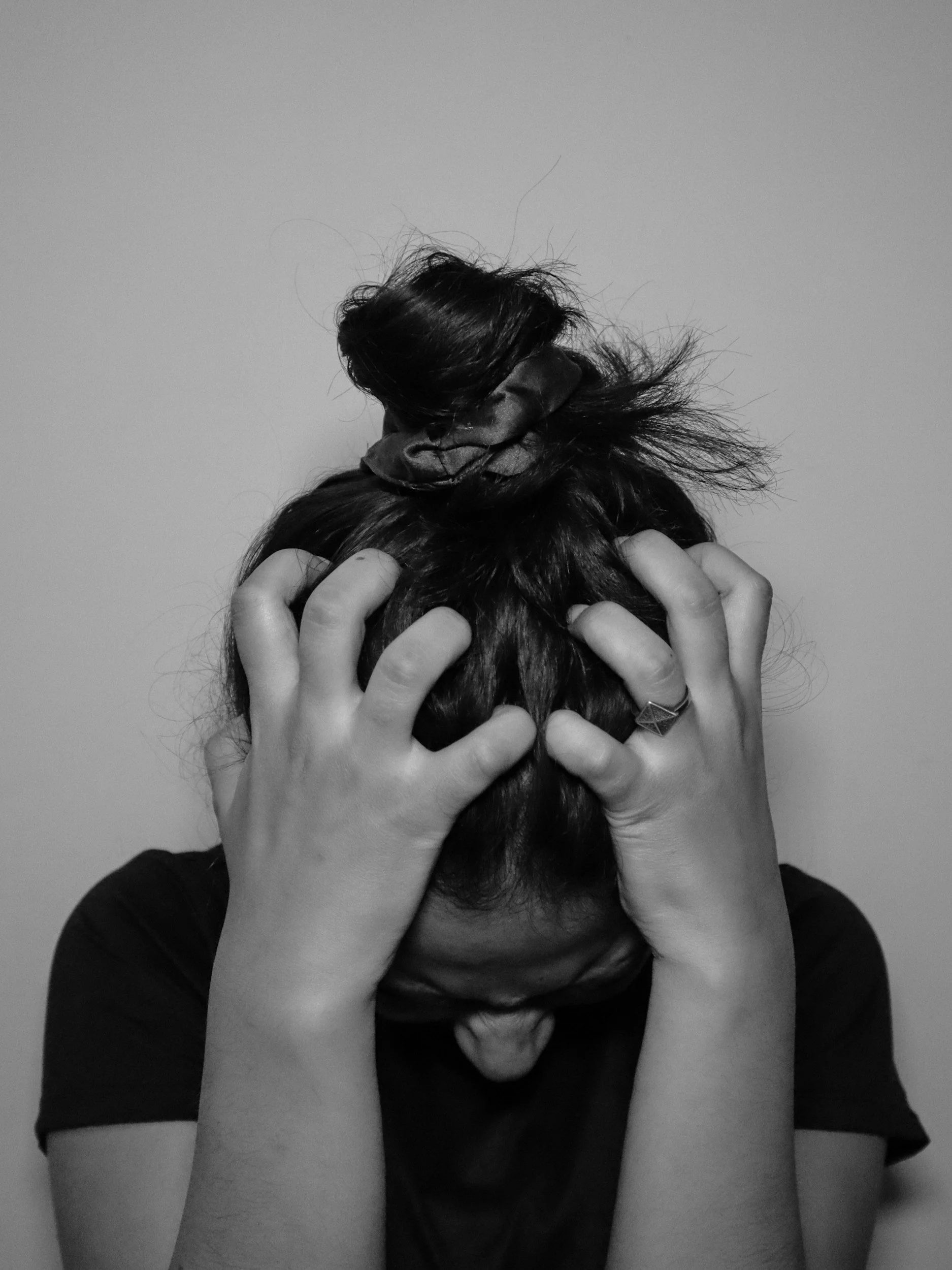

Relational Harm OCD: When Relationship, Harm, and Scrupulosity Themes Collide

Written by: Reece Thomas, CMHC

Harm OCD:

When I first learned about OCD, I really resonated with the phrasing offered to me at the time of having a “hyper-inflated sense of responsibility.” This language has really informed my understanding of many themes of OCD, but especially harm. If you don’t already know, OCD is often categorized into themes such as scrupulosity (which can be religious-focused or more largely concern themes of morality), contamination, relationship OCD and more. Traditionally when I think of harm OCD, I think about egodystonic intrusive thoughts and fears around physically harming others (e.g. “What if I snap and kill my partner?”), which can feel extra scary when you aren’t aware of what OCD is. Hint: it’s not an actual desire to hurt your partner, it’s the fear of doing so.

Two very important aspects of understanding OCD are that the intrusive thoughts are opposite to what the person values (egodystonic) and that OCD often hyperfixates on and makes the person question their values (because you probably wouldn’t be so distressed if you didn’t care about these things!).

That being said, more examples of harm OCD might sound like..

What if I accidentally stab someone with a knife?

What if I just snap and hurt people I care about?

What if I steal a friend’s prescription or something at the store?

If you don’t have OCD and have never experienced these, you might be thinking, “but why would you think that if you didn’t want to do it?”, and that is a huge part of the distress of OCD is that it feels confusing to the person because they know they don’t want to, and yet, their brains like to frame these deeply held values as uncertainties that can cause the person to doubt their own reality and experiences. Further, OCD often starts with “what if” and can include associated mental images or body sensations that make everything feel even more scary and real, when we aren’t aware that these thoughts are not an indicator that you want to do something or are going to, they are just thoughts.

Unfortunately, we live in a world where there are a lot of mixed messages about thoughts. Having grown up religious, it was drilled into my brain that we should have only good, “holy” thoughts and that “bad” thoughts were an indicator of sin or something needing to be addressed, perhaps through repentance or praying more, etc. Even outside of religion, pop psychology teaches us that we can just “think positively” or that “your thoughts become your reality”. These catchphrase-y one-liners might get a lot of attention from the algorithm, but they are not accurate psychoeducation on the nature of thoughts! We cannot control which thoughts pop into our brain, however we can learn to change our relationship to those thoughts, which can alleviate much of the distress and anxiety that OCD brings.

The role of the Obsessive-Compulsive (O-C) Cycle

For people with OCD, these intrusive thoughts become sticky and repetitive, creating an obsessive feeling, often leading to compulsions to try to reduce the distress the thoughts bring. This leads to what is called, the O-C cycle.

Compulsions from the above examples might look like:

Avoiding being near knives or other sharp objects just in case you accidentally stab someone.

Mentally checking to see if the thoughts are present.

Telling yourself you are a danger to others and cannot trust yourself.

Googling things about people who murder or assault others to see if you have any of the “warning signs”

If you experience this personally, you know how much vigilance this can create on a daily basis. If you don’t experience this yourself, imagine trying to navigate all of your usual responsibilities but having a constant background of mental images and scary thoughts questioning you and your values.

Relational Harm OCD:

Something I learned from my therapist was to conceptualize harm OCD outside of physical harm and into the relational realm. This can show up as a blend of relationship, harm, and scrupulosity OCD such as intense fears of being unethical or making decisions that end up causing harm to people at work or in your community. I definitely experienced this in my early work as a therapist where I would be really scared about how an intervention might be received by a client, if I was doing everything right as a therapist or if I was accidentally or unknowingly causing harm by not knowing something or not being constantly aware at all times. This heightened distress can lead to avoidance of taking on new clients, constantly signing up for more trainings and reading more books to make sure I am doing everything I can for my clients, or mentally reviewing sessions to think about if I said anything “wrong” or that could have hurt my clients. I am thankful that I now have more skills and support to address these fears from my own experiences with OCD, and that they don't detract from my work with clients, but in fact, allow me to have more compassion and insight for those with similar thoughts and fears. All that to say, OCD really does latch on to what we value most, and it is a helpful reframe to understand that these fears are not premonitions but rather signals of what I value and of deep care.

We Fixate Because We Care So Deeply

If you don’t or haven’t experienced OCD personally, you might be thinking, “aren’t these things you should be thinking about?” and to some extent, you’re right, we should all be curious about how we impact others. However, part of the issue is that OCD doesn’t always have us examine our impact on others in a meaningful way, it just fixates on insisting that you cannot trust yourself and the worst must be true (e.g. instead of ‘my tone came out kind of harsh, whoops!’ OCD might spin this into ‘I am a mean, careless person that harms others just by speaking’). And one of the saddest parts of this is that these deep fears are coming from a place of deep care, of not wanting to cause others harm because it is painful to do so.

Additionally, we live in a punitive society that doles out disproportionately high punishments all the time. When we take a decolonizing approach to OCD and understand the context, we begin to see that these fears, this “hyper-inflated sense of responsibility” makes so much sense in the context of understanding that there often isn’t room for the rupture and hurt that is inevitable to lasting relationships because the risks of, for examples, having a negative review left by an unhappy client and that impacting your livelihood or associated fears of being talked about poorly in the community and people no longer referring to you – these make it a lot more difficult to honestly check in with ourselves around if we might have acted out of alignment with our values or showed up in a way that we didn’t want to.

Healthy relationships have conflict, but they have repair too

As I write this, I am reminded of how challenging it is that often there is an expectation that a good relationship means no one is hurt and there is never conflict, when that is just not the reality of a secure relationship. Good therapy often involves navigating rupture and repair so that clients can do this in their other relationships outside of therapy, as well.

Hurt vs. Harm

Now, a little note, there is a big difference between hurt and harm, and I think it is important to be on the same page about this. OCD can amplify what is really hurt and make it feel like harm. Activist and author, adrienne maree brown delineates between harm, conflict, abuse, misunderstandings, mistakes, and critique in their book, We Will Not Cancel Us. Clarity around language can help us to engage when we notice ourselves getting stuck in the waves of overwhelming fears. Brown argues that when we collapse harm, conflict, abuse, misunderstanding, mistakes, and critique into one category, we lose the ability to respond in nuanced and liberatory ways.

Here’s a breakdown of each construct as Brown describes them in their work:

Harm:

is an action or pattern that results in real injury: emotional, physical, relational, or material. For Brown, harm is not about intent, but about impact. Harm requires accountability, repair, and often structural change, but it does not automatically mean the person who caused harm is abusive or should be exiled from community. Harm exists along a spectrum and can be unintentional.

Conflict:

Conflict is a natural and inevitable part of being in community. brown reminds us that conflict is not inherently harmful; it often reflects differing needs, values, or worldviews. Conflict can actually deepen intimacy and solidarity when approached with curiosity instead of punishment.

Abuse:

Abuse, in adrienne maree brown’s framing, is not a single harmful incident but a pattern of controlling, violating, or degrading behavior. Abuse involves a power imbalance and an ongoing dynamic in which one person dominates, manipulates, or repeatedly harms another.

Misunderstandings:

Misunderstandings happen when there is a breakdown in communication or interpretation. Rather than harm or malice, misunderstandings are often the result of assumptions, unclear language, or lack of shared context. brown emphasizes that many online call-outs stem from simple misunderstandings that escalate because they aren’t named as such.

Mistakes

A mistake is an error, misstep, or poor decision that may cause impact but was not rooted in malice or an abusive pattern. brown argues that mistakes are part of being human. Calling every mistake “harm” or “abuse” creates a punitive culture where people are afraid to learn publicly.

Critique

Critique is an evaluation of ideas, behavior, or structures with the intention of growth, clarity, or accountability. brown sees critique as an essential tool for movement-building, but they warn against weaponizing critique into character assassination. Healthy critique centers the work, not the destruction of the person doing it.

Reflection Questions:

How do these differentiations land for you?

Have you seen the words harm or abuse over-used, when perhaps misunderstanding or mistake may have been a more accurate reflection?

How might the conflation of critique, mistakes, misunderstands and conflict- with harm and abuse- uniquely impact people who experience these overlapping themes of OCD?

How OCD Latches On

In my early days of learning about OCD, I was taught that we shouldn’t pay attention to the content or themes of OCD because they were “irrational” and “random”. I wholeheartedly disagree with this notion now. In my experiences, both clinically and lived, fears around harm are shaped by experiences. There is a modality for approaching OCD called Inference Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (I-CBT), and I really like how they talk about inferences (aka conclusions). Instead of understanding obsessive thoughts as intrusive and “out of nowhere”, I-CBT postulates that the thoughts are shaped by a variety of experiences including observations, that we then create conclusions out of. For example, I might not have had the experience of a client telling me I caused them harm, but I might have heard others talk about their experiences with this - I have definitely seen this play out in social media! This is one way that OCD applies out of context facts to what could be possible for us. It’s understandable our brain goes to this place and not necessarily relevant to our here and now experience.

Compassionate Accountability vs. Spiraling in OCD’s Doubt

I feel the need to say that the point here is not to dismiss or minimize the importance of recognizing harm and naming it, and then to engage in sincere repair and accountability processes. Quite the opposite, actually, I think the point is to create a space where people can be more honest about these fears so we can actually talk about how to reduce harm. I observe that sometimes, OCD’ers will internalize a lot of our mental thoughts for fear that people will think poorly of us when what we sometimes need is the space to say, “I’m scared”, “how do I come to terms with accepting that as a human, I am capable of and will cause harm just by being in relationship to others and I want to be accountable while also caring for myself.” Transformative justice talks about how even (and especially!) when we cause harm, we also deserve support, and this is what creates true changes.

Final Thoughts

I wonder what would change if we weren’t so afraid of harm that we didn’t talk about it; I wonder how that might open up space for more dialogue and safety to talk about hard things and even prevent more harm because we are prepared for how to address it. I imagine when we get to these roots, there would be less OCD distress.

If you resonate with this and want tools for coping with the relentless rumination and mental checking that can happen with these OCD themes, check out our blog on coping with mental compulsions. If you are looking for OCD therapy or recovery coaching, I would be happy to set up a free consultation call with you! Please reach out or email me directly at: therapywithreece@proton.me or via submitting an inquiry through our website.

Meet the Author, Reece Thomas, CMHC

Reece is an incredibly compassionate human who is specializes in OCD and Eating Disorders through a neurodiversity affirming lens. Reece also works with trauma, BIPOC issues and LGBTQIA+ issues.

Reece offers virtual therapy to folks in WA, UT, MD and TN. Reece also works with folks worldwide via recovery coaching.

Learn more about Reece on their bio page!